Clinical trials in Australia and the HPV vaccine

Every year, girls and women across Australia are immunised against the human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes most cervical cancers.

While cervical cancer continues to kill more than 300,000 women every year, Gardasil, the HPV vaccine, is paving the path towards worldwide elimination of the disease.

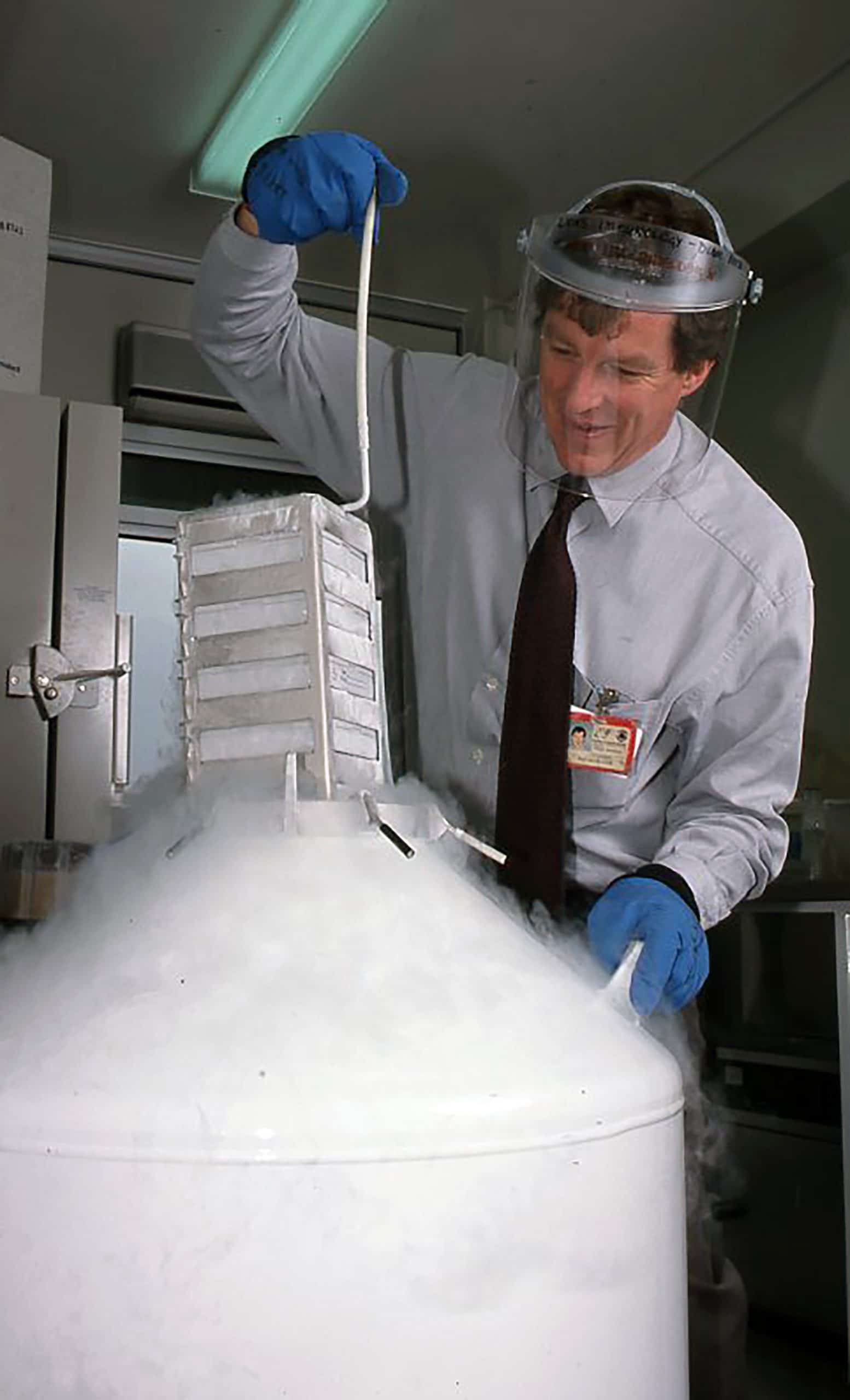

For this, we have immunologist Professor Ian Frazer and his clinical trials to thank. The Scottish born, Australian scientist co-developed the first vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. It is now distributed to all Australian school children aged 12 – 14.

Today, the vaccine is expected as part of Australia’s National Immunisation Program, however, without extensive clinical trials, Gardasil would never have been made available.

Clinical trials are in fact rigorous research studies undertaken by scientists and clinicians who have identified a new treatment and need to analyse its effectiveness. They are usually the product of various teams and resources, and will often start in a lab under a microscope but are enabled by endless hours of data analysis.

Clinical trials are vital for people living with cancer and are the only reliable means for doctors to identify which treatments work and which don’t. It’s also likely most of us have a fairly narrow understanding of what a clinical trial actually involves.

So, if you’re imagining a savvy professor having an “aha” moment in a research lab, you’re probably oversimplifying things.

Cancer clinical trials are designed to answer a range of research questions and will target either the broad population, or specific demographics with a high chance of developing a certain cancer. If a trial identifies that a particular treatment is more effective than current care options, it may be used for future patients.

Australia has very specific guidelines for cancer clinical trials, which are governed by the NHMRC (National Health and Medical Research Council) and the TGA (Therapeutic Goods Administration). They will assess if a medication is safe, how well it works and whether there are any side effects.

A clinical trial must demonstrate that a new treatment is both effective and safe before it can be distributed. Development for the HPV vaccine first began in the 1990s before Gardasil was declared approved for widespread use in 2006.

Studies involving close to 21,000 girls and women were conducted to evaluate Gardasil’s safety and effectiveness before the vaccine received TGA approval.

The studies revealed that the vaccine is almost 100% effective in preventing precancerous lesions caused by the two main types of HPV that are associated with cervical cancer. If these trials hadn’t taken place, there would be no way to protect against cancer causing HPV infections.

Since 2007, more than 200,000 million doses of Gardasil have been distributed to over 130 countries worldwide. In the decade since the vaccine was approved, the HPV infection rate in countries with high immunisation levels, including Australia, was lowered by up to 90%.

Ian Frazer considers the vaccine to be the single most effective way to prevent women from developing cervical cancer.

‘Rivalling the end of polio in terms of shear impact on humankind.’ Professor Ian Frazer.

Australia is now making strides to eliminate cervical cancer by 2030. This success can be attributed to the country’s HPV vaccination program in conjunction with its National Cervical Screening Program.

Australia’s efforts are being felt by the world over and are playing a huge role in reducing rates of cervical cancer for women everywhere.

*All images courtesy University of Queensland, Australia

Do you think it’s time we all took action towards worldwide cervical cancer elimination? Join the movement and sign up to the campaign today. We’d also love to hear your feedback on this story, so please post your comments to us below. You’ll also find us on all the usual social channels.