Conquering cervical cancer in Australia: the early days

A personal reflection by David Hill, former Cancer Council Victoria Director

One way and another, I have spent a long time in a field we used to call “public education about cancer”. At the time I began in the early 1960s the messages to the public were limited to recognition of the seven early warning signs of cancer. Only one of these – “any unusual bleeding or discharge” – was relevant to cancer of the cervix. At the time, it was the best advice we had to offer. In truth though, a patient presenting as soon as she noticed such a symptom, would not have a very large survival advantage.

What was needed was a way to give the treating surgeons a head start by finding the signs before the person even noticed them.

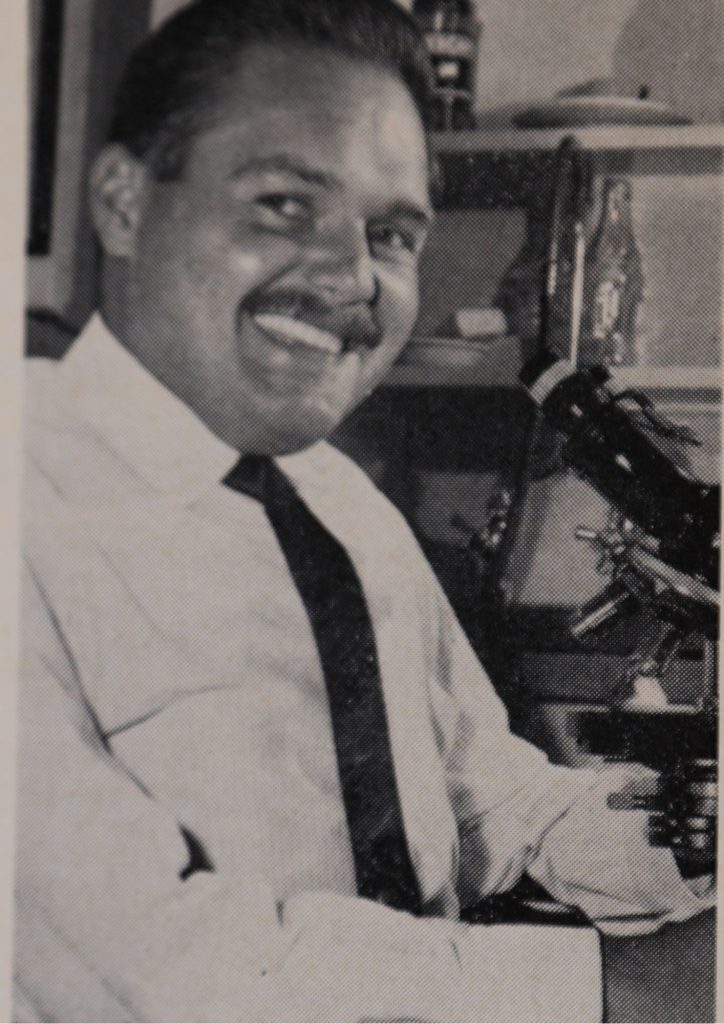

So, the advent of what in Australia was variously called the Pap test, the smear test, and the cell test, caused a lot of excitement in Victoria. The pioneering research and early implementation programs were done in Canada by Dr George Papanicolaou, and others.

Image above: Dr George Papanicolaou, a pioneer in cytopathology and early cancer detection, and inventor of the Pap smear.

The Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria, for which I worked at that time, was quick to recognise the importance of cervical cytology to detect cancer very early and prevent death from the disease. But to achieve this a whole system and service had to be set up to deliver the life-saving potential to women at risk of cervical cancer. At that time, it was understood that women over the age of 18 who had commenced sexual activity were most at risk of developing cervical cancer in Australia. Victoria was one of the earliest jurisdictions to adopt cervical cancer population screening. The planning and resourcing needed to achieve this are probably typical of the experience of many other jurisdictions around the world which also embraced this new opportunity to detect a common form of cancer early.

The first requirement was to acquire the specialist medical expertise to lead the program locally. In the early 1960s a young pathologist, Dr Michael Drake, was sent to Canada to be trained in techniques for identifying in smears the microscopic changes that signify beginning cancer. Smears are usually collected by a woman’s GP during a medical examination. These are then sent to a central laboratory. While the medically-trained pathologist was always the one to make a ‘positive’ call on a slide, a team of cytotechnologists were hired to take the first look under a microscope at thousands of slides coming in to the laboratory. Slides they considered suspicious were referred to the pathologist for final assessment.

The second requirement was to train a workforce of cytotechnologists. No particular prior qualification was needed, but they had to be meticulously observant and prepared to sit at a microscope all day.

Image right: A cytotechnologist in the laboratory, They evaluated patients’ cell samples and were trained to notice subtle changes.

The third requirement was to set up and equip a dedicated laboratory to examine thousands of slides every week. In Victoria, this lab was established in a large public hospital, and later the cytology service was housed and managed independently.

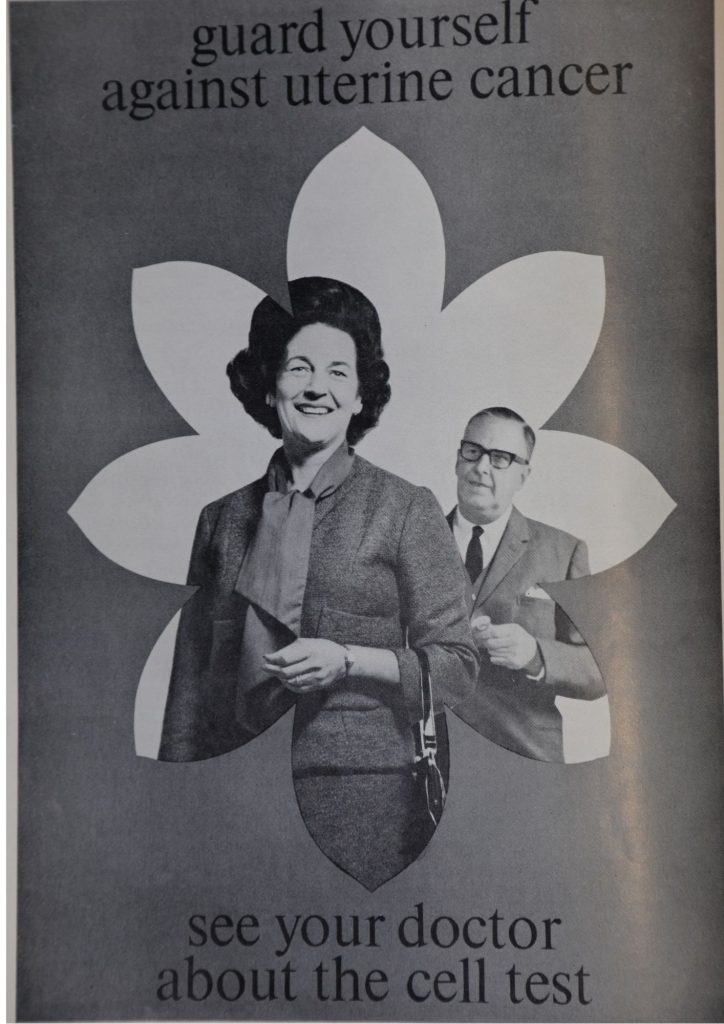

The fourth requirement was to have a general practitioner workforce trained and willing to take cervical smears at the standard required. Of course, GPs are already trained to do a pelvic examination, but it was also necessary to upskill them in taking a sample of fluid (the smear) from the cervix and placing it on a slide to be sent to the cytology service. This upskilling was achieved mostly through mail outs to doctors, printed communications, lectures and workshops organized by the Anti-Cancer Council. GPs were also urged to recommend the test to their patients. To help them do this, waiting room posters and leaflets for patients were provided to be used in general practice.

Image left: Posters like this one were hung in general practice waiting rooms.

Finally, it was necessary for women targeted for screening to be sufficiently informed and motivated to participate. Having trained in psychology, this aspect of the problem intrigued me. In fact, my very first independent research paper (which I presented at the International Cancer Congress in Houston, Texas in 1970 and which was published in the Medical Journal of Australia) was entitled “Attitude and Behaviour Correlates of Cytological Screening in Women”.

Image above: A patient is informed about cervical cancer screening.

From doorstep interviews with a random sample of nearly 300 women, I found that about 4 in 10 women had been screened and of these 40% of the tests were done on the patient’s initiative and 60% at her doctor’s prompting. Findings about the relationship of screening status with age, socioeconomic status and neighbourhood were useful in planning future campaigns to lift participation rates. It was also possible to use the survey data to explore the relationship between participation and worry about cancer and fear of getting a cancer diagnosis from the test. Understanding something of the psychology behind cancer-related behaviours (such as screening, smoking, sun exposure) is vital in crafting effective messages and strategies to change behaviour and prevent deaths from cancer.

This model, in which the various cancer prevention campaigns are grounded in behavioural research became a hallmark of the Cancer Council’s program. It is a feature that has endured to this day.

See www.cancervic.org.au/research/behavioural

Since those early days of the Pap test, there have been major developments that have seen the cervical cancer death rate in Australia significantly reduce. In Victoria, it has dropped from 3.6 deaths per 100,000 women in 1982, to 1.0 deaths per 100,000 women in 2019. Services, systems and campaigns to achieve very high levels of cytological screening drove those results. A state-wide Registry was established in 1989 and this recorded every Pap test and recalled women due for their next test regularly thereafter. Mass media campaigns have played a major part in getting participation rates as high as 69% of the target population in 1999.

The next stage in fighting cervical cancer is as transformative as was the development of the Pap test. The discovery of the virus (HPV) responsible for most of these cancers has led to a vaccine that is best deployed in early teenage years – the ultimate preventive strategy. The HPV vaccine, coupled with regular cervical screening, suggests Australia is truly on the threshold of fully conquering this lethal cancer.

Professor David Hill AO

Do you think it’s time we all took action towards worldwide cervical cancer elimination? Join the movement and sign up to the campaign today. We’d also love to hear your feedback on this story, so please post your comments to us below. You’ll also find us on all the usual social channels. With widespread global coverage of the HPV vaccination and dedicated cervical screening programs, it will be possible to eliminate cervical cancer for future generations. Follow Conquering Cancer on Twitter | Facebook | LinkedIn | Instagram